Phorpiex Phishing Campaign Delivers GLOBAL GROUP Ransomware

0 minutos de lectura

Lydia McElligott

We recently observed a high-volume Phorpiex campaign delivered through phishing emails with the subject "Your Document.” It’s a subject line that’s been heavily used in largescale campaigns throughout 2024 and 2025.

The phishing email includes a seemingly harmless attachment that is in fact a weaponised Windows Shortcut (.lnk) file. This malicious shortcut highlights how attackers continue to exploit everyday file types to gain an initial foothold in a victim’s system.

By combining social engineering, stealthy execution, and LivingofftheLand (LotL) techniques, the file silently retrieves and launches a second stage payload without raising suspicion.

Here’s the attack chain:

Fig. 1 - Attack chain

Why LNK Attachments Still Work

Windows shortcut files are still one of the simplest ways to turn a single click into code execution. In inboxes, a .lnk can be disguised as a normal document by using double extensions (for example, Document.doc.lnk) and relying on Windows default settings that hide known file extensions. To most users, the filename reads like a Word document, not a shortcut that can launch commands.

Attackers also lean on familiar visual cues. By borrowing icons from legitimate Windows resources like shell32.dll, the attachment can look like a trusted file type at a glance. That mix of “document-looking name” plus a recognisable icon reduces hesitation, especially in high volume phishing where the goal is speed and scale.

Once clicked, a shortcut can execute cmd.exe or PowerShell directly, pass arguments quietly, and chain actions without dropping an obvious installer. That low-friction path is why LNK lures keep showing up in commodity campaigns: they are easy to generate, easy to theme, and they reliably bridge the gap between a phishing email and a payload download.

Analysing the Email Sample

Fig.2 - Phishing email sample

The attachment file is named Document.doc.lnk, a classic trick that relies on Windows hiding the .lnk extension. To the victim, it appears to be a normal Word document. Metadata shows the shortcut uses an icon from shell32.dll, completing the illusion with a familiar document-style icon.

Execution Flow at a Glance

1: User opens the phishing email and sees an attachment that appears to be a document (double extension).

2: User clicks attachment which is actually a Windows shortcut (.lnk).

3: The shortcut launches cmd.exe with embedded arguments (no visible installer).

4: cmd.exe invokes PowerShell to run a download-and-execute sequence.

5: PowerShell pulls the payload from a remote URL (HTTP/HTTPS) and writes it to disk.

6: The downloaded file is saved in a system-like location and name, for example:

- C:\Windows\windrv.exe

7: PowerShell (or cmd.exe) executes the dropped binary (often via Start-Process).

8: The ransomware then proceeds into local execution mode (including “mute” behavior) and begins its run sequence.

Fig. 3 - Email attachment

The metadata also shows a creation date of May 2024, suggesting the attacker either reused an older LNK template or maintained dormant infrastructure before launching this campaign. When executed, the shortcut silently launches cmd.exe in the background, which in turn invokes PowerShell to retrieve a remote payload. The file spl.exe is downloaded from 178[.]16[.]54[.]109 and written to %userprofile%\windrv.exe, a name chosen to resemble a legitimate Windows driver. PowerShell then executes the newly dropped file via StartProcess, completing the second stage delivery without any visible activity to alert the user.Processstage delivery without any visible activity to alert the user.

Phorpiex is a modular Malware-as-a-Service botnet that has been active since roughly 2010. It is commonly used to distribute secondary payloads such as ransomware, cryptominers, and spam components. Its operators often rely on lightweight downloaders delivered through phishing campaigns to initiate their infection chains. In this case, the infection chain ultimately leads to the deployment of GLOBAL GROUP, a Ransomware‑as‑a‑Service (RaaS) operation that emerged as a successor to Mamona ransomware.

What Makes GLOBAL GROUP Different

GLOBAL GROUP ransomware diverges from traditional ransomware families by operating in a fully "mute" mode. Instead of contacting a command‑and‑control (C2) server, it performs all activity locally on the compromised system. The ransomware does not retrieve an external encryption key; instead, it generates the key on the host machine itself. As a result, despite the claims made in its ransom note, GLOBAL GROUP conducts no data exfiltration and is fully capable of executing in offline or air‑gapped environments. This offline‑only design also increases its likelihood of evading detection in networks where monitoring efforts rely primarily on observing suspicious or anomalous traffic.

In this instance, the ransomware is written to disk as a binary masquerading as a legitimate Windows executable named windrv.exe.

Fig. 4 - Command prompt launches PowerShell

Static analysis shows the GLOBAL GROUP sample is not packed. The binary is highly verbose, and much of its behaviour can be inferred from its embedded strings. Originating as a commodity malware, the sample contains several modules that can be readily identified.

Key Behaviours and Defensive Telemetry

The ransomware uses a ping command as a simple timer before removing itself from disk to impede forensic analysis.

Fig. 5 - Ping command strings

This command spawns a new instance of the command processor, which sends three ICMP echo requests to the unusual loopback address 127.0.0.7. Because Windows introduces approximately a one‑second delay between each ping, the -n 3 option results in a roughly three‑second pause. This delay allows the ransomware to complete its execution and terminate cleanly from memory. Once the ping sequence finishes, the final portion of the command deletes the ransomware binary from disk, reducing available artifacts for later forensic investigation.

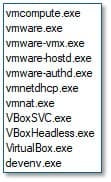

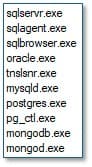

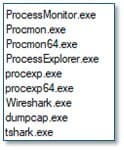

The malware includes anti-virtualisation and anti-analysis functionality by enumerating running processes on the host system. It checks for processes associated with virtualised environments used in malware analysis and sandboxing, and for common analysis tools. Additionally, it identifies database-related processes and terminates them to release file locks, thereby increasing the volume of data available for encryption.

Fig. 6 - Visualization strings

Fig. 7 - Database-related strings

Fig. 8 - Analysis tool strings

The cleanup module establishes persistence by copying itself to %windir%\Temp\cleanup.exe and creating a Windows service configured to start on demand. It uses the Task Scheduler to create a task named "CoolTask" that executes at system startup with SYSTEM privileges, triggers it immediately, and then deletes the scheduled task to reduce its forensic footprint while maintaining persistence through the service.

Fig, 9 - Cleanup module strings

The sample supports lateral movement and network propagation. It leverages ACTIVEDS.dll and performs LDAP queries to harvest information from Active Directory, enabling it to enumerate domain objects and identify additional endpoints within the network. The malware is also capable of creating Windows services on remote machines, facilitating automated deployment across the domain. Using ADVAPI32.dll, it can interact with credential‑handling functions, allowing it to impersonate users, including escalating to a domain administrator. In addition, the sample includes mechanisms to manipulate or clear event logs, helping it conceal its activity and hinder forensic analysis.

Fig. 10 - LDAP spread strings

Fig. 11 - Worm capabilities in strings

The ransom note is embedded directly into the binary.

Fig. 12 - Ransom note in strings

Fig. 13 - Delete shadow copies in strings

Fig. 14 - Delete shadow copies process

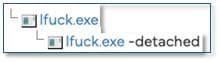

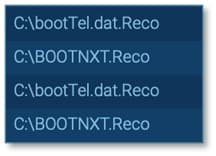

During execution the GLOBAL GROUP ransomware launches an instance of itself in a detached process. This temporary executable conducts the primary ransomware functionality. It encrypts user files and documents across multiple directories appending the files with the extension .Reco.

Fig. 15 - Executable chain

Fig. 16 - Encrypted files

Files are encrypted using ChaCha20-Poly1305 encryption algorithm. This version (used by GLOBAL GROUP) is much more robust than earlier Mamona samples for which decrypter tools are publicly available. ChaCha20-Poly1305 uses Authenticated Encryption (Poly1305), which means the file cannot be tampered. Decryption is not possible without the attacker’s private key.

A README.Reco.txt ransom note is dropped to various locations on the compromised host. The attackers direct victims to communicate via a Tor based onion site on the dark web.

Fig. 17 - Processes dropping ranom note

Fig. 18 - README ransom note

GLOBAL GROUP can be identified in a few different ways. First, the malware replaces the user’s desktop wallpaper image with a message stating the system has been compromised by GLOBAL GROUP.

Fig. 19 - Actual ransome note

Another identifying feature is the presence of the mutex Global\Fxo16jmdgujs437, visible within the malware’s strings. Malware authors commonly use mutexes to prevent multiple instances of the same malware from running simultaneously on a single system.

Fig. 20 - GLOBAL GROUP mutex

Additionally, encrypted files contain a unique file marker - xcrydtednotstill_amazingg_time!!, which is characteristic of GLOBAL GROUP. This marker can be observed by inspecting an encrypted file in a hex editor.

Fig. 21 - GLOBAL GROUP file marker

Key Lessons from a Low-Noise Ransomware Chain

This campaign demonstrates how long-standing malware families like Phorpiex remain highly effective when paired with simple, but reliable phishing techniques. By exploiting familiar file types such as Windows shortcut files, attackers can gain initial access with minimal friction, enabling a smooth transition to high-impact payloads like the GLOBAL GROUP ransomware.

Its fully offline execution, local key generation and aggressive artifact removal make detection and recovery particularly challenging. This trend toward quiet, self-contained ransomware underscores the importance of prioritising endpoint behaviour monitoring over network activity alone.

Protection Statement

- Lure – Phishing email and .lnk attachment downloader are blocked by email analytics and web analytics

- Payload – Downloaded ransomware is added to our malicious hash database

IOCs

| Document.zip.lnk | 70a4afab44d6a9ecd7f42ab77972be074dec8383a47a2011eb0133a230a4fae3 |

| Dropper | http://178[.]16[.]54[.]109/spl.exe http:// 178[.]16[.]54[.]109/lfuck.exe |

| Spl.exe/ lfuck.exe | 55f3a2d89485bb40ea45e5fa1f24828f71a81ef4ccc541b6657fc7a861ef3add |

| Mutex | Global\Fxo16jmdgujs437 |

| Ransom note | README.Reco.txt |

| Encrypted file extension | .Reco |

| Encrypted file marker | xcrydtednotstill_amazingg_time!! |

Lydia McElligott

Leer más artículos de Lydia McElligottLydia McElligott is a Security Researcher with the Forcepoint X-Labs Threat Research team. She focuses on researching cyberattacks which target the web and email, particularly focusing on URL analysis, email security and malware campaign investigation.

- Future Insights 2026

En este post

Future Insights 2026Leer el Libro Electrónico

Future Insights 2026Leer el Libro Electrónico

X-Labs

Reciba información, novedades y análisis directamente en su bandeja de entrada.

Al Grano

Ciberseguridad

Un podcast que cubre las últimas tendencias y temas en el mundo de la ciberseguridad

Escuchar Ahora