X-Labs

Get insight, analysis & news straight to your inbox

Unmasking the Lumma Stealer Campaign

Jyotika Singh & Prashant Kumar

May 7, 2025

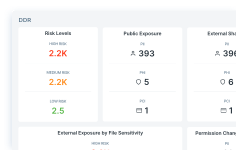

How DSPM Helps You Identify and Prioritize Risky Data

Tim Herr

May 6, 2025

Ensure Data Compliance with One Simple Framework

Tim Herr

May 1, 2025

FormBook Malware Distributed via Horus Protector Using Word Docs

Lydia McElligott & Prashant Kumar

April 28, 2025

The Return of Pharmacy-Themed Spam

Hassan Faizan

April 25, 2025

Introducing the Forcepoint Data Security Cloud Platform

Corey Kiesewetter

April 29, 2025

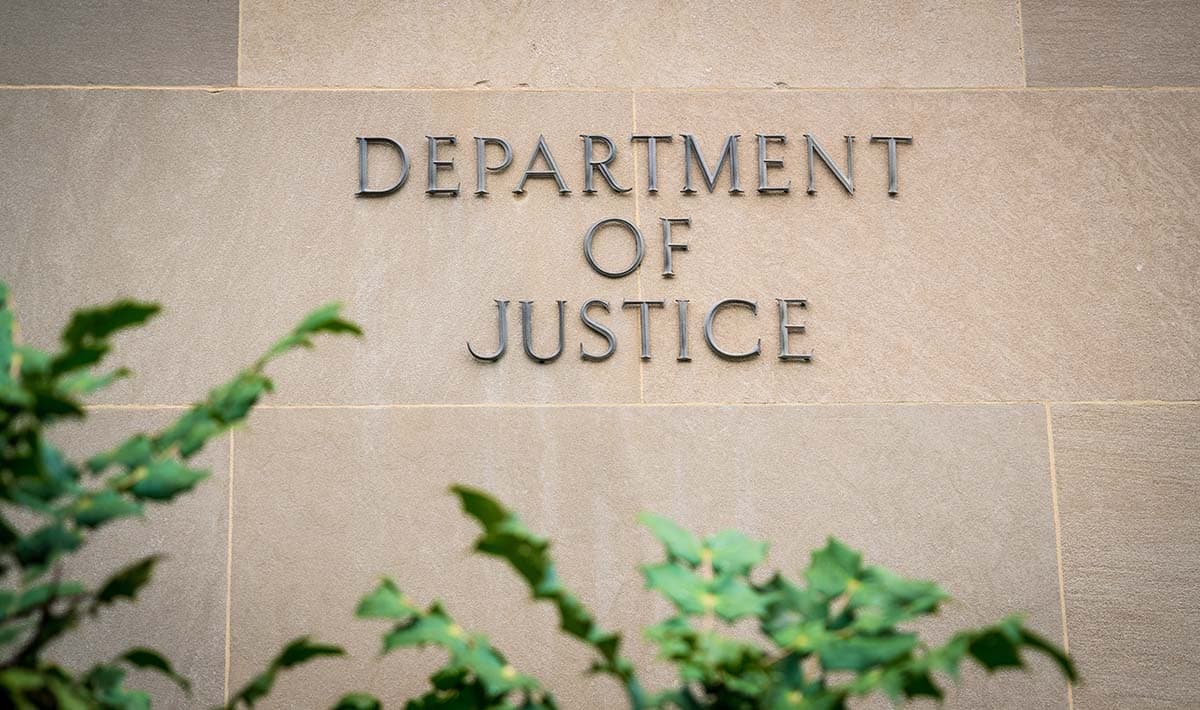

The DOJ’s Data Security Program: What You Need to Know

Lionel Menchaca

April 24, 2025

Extending DLP Controls to Eliminate Blind Spots in Web and Cloud Data Security

Corey Kiesewetter

April 24, 2025

How to Efficiently Identify and Prioritize Sensitive Data

Tim Herr

April 22, 2025

The 23andMe Bankruptcy and Genetic Data Security

Tim Herr

April 18, 2025

Data Security Insights from the 2025 Gartner® Market Guide for DLP

Tuan Nguyen

April 17, 2025