Part 2 - The Ghost of Ransomware Yet To Come

0 min read

In this Part 2 of the history, present and future of ransomware (read Part 1 here), we take a closer look at how malicious techniques and software have developed over time, and what types of ransomware and techniques of extortion might be yet to come.

Actors and weapons of nowadays

Netwalker

Netwalker is one of the most successful ransomware groups of the past year. Focusing predominantly on high profile targets, they have managed to compromise more than enough to make a name for themselves. They are known for establishing an extended foothold in the target environment such that they can accumulate enough knowledge about the internal infrastructure, credentials, and other vital information necessary to exfiltrate valuable data. The stolen intellectual property is then used to apply extra pressure if the victim is unwilling to pay the ransom. Due to events of recent years companies are better prepared for the unexpected, they are implementing and deploying data and disaster recovery strategies that also cover ransomware infection. However, the stakes are higher when it is not just the prospect of data being lost, but its theft - or worse, publication - which would not only damage reputation, but may incur legal consequences due to data compliance failures.

Netwalker is believed to target internet facing services such as Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP), either by exploiting vulnerabilities or brute forcing their way in. Once inside, they use a combination of privilege escalation exploits - collected mostly from GitHub -, well-known offensive tools such as Mimikatz and NLBrute, and both custom and free uninstallers for specific security products. Their primary aim is to gain privileges of a domain administrator. Once this has been obtained, access to data for exfiltration, and distribution of the ransomware payload is trivial. For the latter they prefer to use a heavily obfuscated custom PowerShell script with the ransomware component embedded within it.

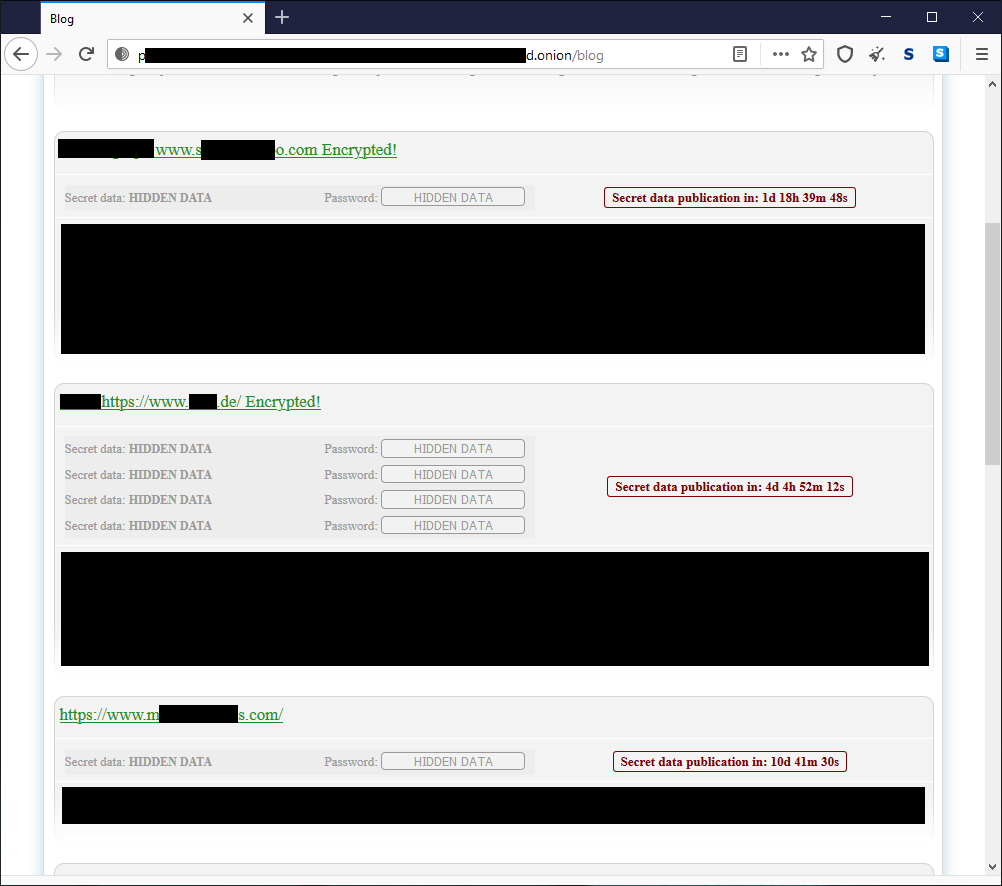

Additionally, the Netwalker gang is one amongst the increasing number of ransomware groups who have introduced a “wall of shame”. If a victim refuses to pay the ransom, then not only will their data be leaked online, but they will also suffer the ignominy of being added to the Netwalker wall of shame. They provide a time frame for the victims to pay up and the countdown is clearly showcased on the wall of shame site along with screenshots for proof of the stolen data. Through the inspection of dozens of different campaigns, we can see that there is a strong preference for targets in the automotive, energy and healthcare industries, but they aren’t shy of picking on law firms, clothing retailers and schools either.

Dharma

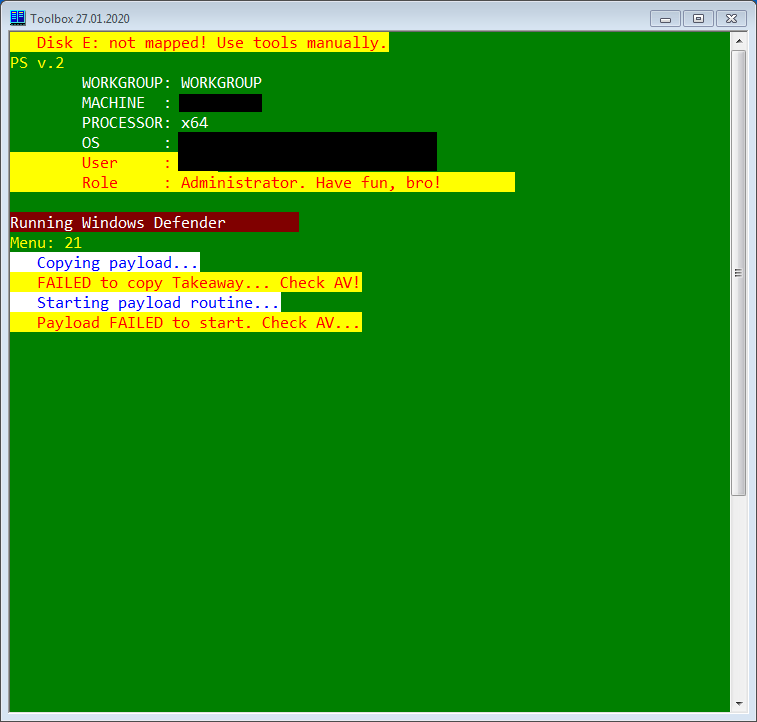

Dharma is another well-established name in the ransomware space whose history goes back some years now. Instead of focusing exclusively on high-profile targets, Dharma’s approach is more about finding lots of small to medium sized companies. The reason for this lies partly in how they work with their affiliates. While we believe the Netwalker group to be working with the higher echelons of the cybercriminal food chain, Dharma is trying to cover a different portion of the market by teaming up with those who are willing, but less talented. This is clearly reflected in their internal toolset (what they've been building and maintaining in the past 3-4 years) which consists of freely available penetration testing and password recovery tools, privilege escalation exploits - also mainly collected from GitHub - custom AutoIt based packages, and password brute-forcers. One of which, interestingly enough, is the exact same cracked version of the NLBrute application used by Netwalker. For convenience, all these tools are wrapped in a helper toolbox created in PowerShell. The toolbox is driven by simplistic commands, but significant documentation and support is provided so that their affiliates – despite their pinched skills – are capable of breaching systems without the level of handholding that would otherwise be necessary.

Like Netwalker, Dharma targets the weaknesses of RDP, but also seems to use stolen credential packs available on the dark web. Once the target has been breached, the toolbox is equipped with enough commands for credential stealing, lateral movement and malware deployment. The occasional use of exepackers (mainly VMProtect) on the compiled exploits indicates they do not have full confidence in their AV-evasion and removal capabilities.

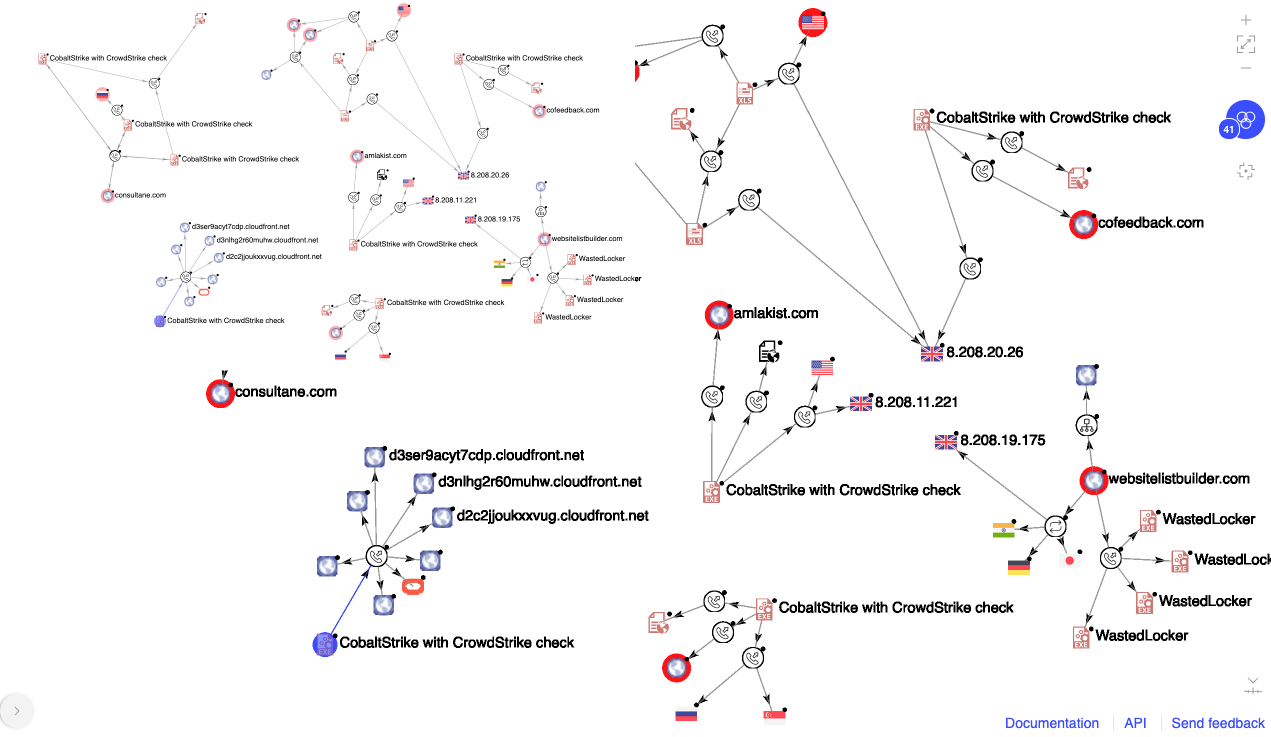

Evil Corp - WastedLocker

WastedLocker is a relatively new family in the ransomware space and, as with Netwalker, the actors behind WastedLocker also prefer high profile targets and often customize their ransomware modules accordingly. While the malware family itself is new, the creators behind it have long been known as Evil Corp. Their reputation was originally established with the creation of the Dridex banking trojan back in 2011. This isn’t their first ransomware creation attempt either, previously the BitPaymer family was also linked to the group. A key difference from the groups mentioned above is the use of a well-respected offensive security toolkit called Cobalt Strike. It allows them to get a foothold within the target environment, and subsequently download and execute further tools to extend their persistence. From there it’s the same pattern seen previously, being patient, moving laterally, crawling their way through domain level access and finally deploying the ransomware binary. To avoid detection by the deployed security solutions, they often utilize exepackers on top of the Cobalt Strike beacon and ransomware payload. The former is strengthened even further by the addition of a valid security certificate – for example, signed by Elite Web Development Ltd. They are careful about not using the same signing certificates for too many different campaigns. Interestingly, there is a specific CrowdStrike AV software based check in most of their Cobalt Strike beacons, even if the target environment is utilizing a different security product.

The responsibility of the penetration testing market

While investigating the various TTPs of the different ransomware actors, another commonality become evident; they show zero interest in reinventing the wheel, instead they use just about anything available on the (black) market or for free on GitHub or similar. Popular and freely available tools such as Mimikatz and BloodHound were originally intended for penetration testing purposes, yet they also ended up being the primary weapons for most affiliates. On one hand, controlling the use of these tools is impossible. It is just too easy to grab the source code, customize it a bit, recompile the binaries and use them for whatever intent one might have. On the other hand, there is a clear market for professional grade tools in this domain. Cobalt Strike, Metasploit framework and the likes are intended to be used to help companies identify their security frailties. They are complex tools and as such they are quite expensive. However, due to the effectiveness of ransomware, cybercriminals are able to acquire these and put them to a more nefarious use. One way to resolve this could be the introduction of stringent background checks when selling a new license, but any regulation around this must be introduced in a way which does not negatively impact on the legitimate sale and use of such tools.

What might come next: The shape of ransom to come

After witnessing enough of the ransomware landscape’s past and present, we are seeing some trends and directions it might take in the future. Let’s have a look separately at the various aspects.

Encryption

It took a while for ransomware authors to find the right balance between performance versus security, but once they corrected the early mistakes of weak crypto choices and implementation issues, their victim’s data was made irrecoverable without the necessary encryption keys. That also meant that the combination of AES+RSA was quickly adopted by most of the actors in the ransomware space. There is no real need for further development in the encryption area, however REvil authors claimed to have switched over from RSA to ECC (Elliptic-Curve Cryptography) due to a small boost in performance. Whether that performance increase is worth the time and effort spent on it, or just about showing off, is hard to tell.

Platforms

The vast majority of ransomware families seen so far have been created for the Windows platform. As focus shifted from home users to corporations, the need to support additional operating systems - especially ones with the primary role of data storage will become more pressing. Linux is the underlying platform of choice for most data centers, cloud services and in-house corporate storage deployments. We can expect that macOS and Linux - and its various incarnations, for example OSs on NAS boxes - will gain additional priority in the near future. There have been numerous attempts in this direction already and it is safe to assume this trend will continue.

Additionally, recent developments focus on the use of virtual machines. Instead of deploying the usual ransomware executable to all hosts, adversaries would spread a highly customized virtual machine with the ransomware payload inside. The advantages of this are twofold, it helps in evading security products and also makes the recovery of the encryption component challenging by incident response teams.

Toolset

Even though there are differences in how each group operates and what toolset they work with, they seem to share one basic principle. Recycle whenever possible. They simply take whatever is up for grabs, as long as it is suitable for the job. From a piece of exploit PoC (Proof of Concept) or compiled binary located at a GitHub repository, through freely available password retrieval tools and credential dumpers, to leaked or cracked copies of well-known commercial penetration testing suites, they don't mind at all. They are working by principles of simple economics, whatever they can grab is reducing the time to (re)create it on their own and they would rather invest that time into looking for new targets and executing the attacks. That’s where the money is.

Delivery

The affiliate-based programs turned out to be very profitable for all parties involved. Everyone can carry out the bit they know the best, the RaaS providers can focus on creating and supporting ransomware packages while also stepping away from the actual attacks. The affiliates can continue breaking into systems without the need to be able to code their own malware or custom tools. They all get their share of the ransom paid and that money keeps the whole ecosystem alive and well. It is expected that most major ransomware groups are going to adopt this approach if they haven't already.

Exaggerated extortion

Everything seemed much simpler when ransomware attacks were only about encrypting files and hard drives. A semi-decent data backup strategy used to be enough to restore any data that was affected post-breach. Not anymore. The risk of data exfiltration has upped the ante by bringing a new dimension to the risk of a ransomware infection. It is no longer just about restoring business continuity, but preventing the loss of valuable IP and years’ worth of brand credibility.

But what else? Ransomware actors have already started to push the boundaries even further, DDoS-ing the victim's infrastructure is an emerging technique, especially against small and medium sized businesses who often have little to no protection against this type of attack. For businesses like this, being offline even for a couple of days could be just as damaging as data theft. Another recent development is the use of Facebook advertisements – with the help of hacked accounts – that publicize the fact that a target has been hacked, along with suitable evidence, just in case the victim decides to deny the fact. This can reach a multitude more people than walls-of-shame operated on the dark web.

By now, it’s clear that ransomware groups are more than just creators of malware. They are manipulators of human behaviour, and will use tricks and techniques explicitly designed to leave the victim no choice but to return to the negotiating table. The prices are far from set in stone either. Agreeing on the price of the ransom is a negotiation where both sides try to reach an agreement.

Conclusion

Ransomware is an ongoing and continuously evolving threat for organizations of any size or scale. Its evolution in recent months was less focused on the technical aspects of the various malware families, and more on how targets had been compromised, what additional steps are taken before the encryption phase, and how those responsible can try and persuade, bully and cajole their victims to the negotiating table. This business model can only be successful if there are enough meaningful targets who are actually willing to pay the ransom. Unfortunately, recent history shows that to be the case.

It cannot be repeated enough that paying the ransom does nothing but validate the investment into these attacks by cybercriminals. Even if online publication is avoided, there is no guarantee that stolen data won’t be silently offered to private buyers. By paying up, victims are continuing to feed the beast. Rather than simply hoping for the best, or paying any ransom after the event, organizations need to plan and prepare for a future in which ransomware is a real and prevalent threat. Defenses can be put up against ransomware. A multi-layered, cloud-enabled SASE-based solution can protect data against these attacks. While improved solutions will mean increased investment into cybersecurity, it is far better to spend money on your own systems, rather than handing it straight to criminals.

- Forcepoint Advanced Classification Engine (ACE)

In the Article

- Forcepoint Advanced Classification Engine (ACE)Read the Solution Brief

X-Labs

Get insight, analysis & news straight to your inbox

To the Point

Cybersecurity

A Podcast covering latest trends and topics in the world of cybersecurity

Listen Now